We’re All Soil Farmers Now: Actively Mitigating Climate Change With Hemp

As we dance toward triple digits again here in New Mexico today, I’m just in from the hemp field for breakfast, sipping my hemp/ginger shake and watching the usual millennial wildfires from my porch office perch. Ho-hum: another spring, another 30,000 or 100,000 acres torched in my backyard. This year’s blaze has been burning for almost a month now. Hopefully the recently erratic monsoon rains will come on schedule later this month. Sometimes it seems like the clouds are gathering. Cheerleading them hopefully from a hemp-and-vegetable field, one sees how rain dances were invented.

We hemp farmers do more than dance though. My hemp crop and yours is actively mitigating climate change. As long as you cultivate regeneratively and outdoors in your own native soil, with no plastic sheeting or synthetic chemicals, you are part of humanity’s long-shot, bottom-of-the-ninth comeback opportunity.

I speak from experience. It’s hard to overstate the dramatic temperature, moisture and air-clarity difference between inside the late-July canopy of a hemp field in the middle of a wildfire (I’ve cultivated in such a shouldn’t-be-normal situation three times and counting) and the conditions maybe ten feet outside the same field. It’s like two different planets. Or maybe two different futures.

I’m thinking today of the cool, moist Oregon field my colleague Edgar Winters and I grew while surrounded by a few hundred thousand acres of wildfire in 2018. As the seed and flowers matured, we often sat down, smack dab in the middle of the field, just for relief. Embraced by the plants we had planted seven weeks earlier, we could feel the carbon being sequestered in the very loamy consistency of the dank, rich soil where we sat, watching the hundreds of thousands of hand-shaped, contented leaves waving to us from seven feet above. Forever more, we palpably understood the impact regenerative farming around the world can have on humanity’s climate change mitigation project.

I’m feeling it again this year already in my Ranch polyculture garden (we have watermelon, pepper and tomato plant hugging some of our hemp), though the hemp plants are still young. This is victory: when hemp is just another plant in the garden (although guess which of these plants is the only one I had to pay for a $700 permit in order to grow my family superfood?). Again, I sit in moist soil with smoke on the horizon.

This saving humanity, my fellow hemp farmer/entrepreneurs, is an integral component of our industry-leading brand: by supporting the products grown and marketed by independent, farmer-owned hemp enterprises, a customer is helping allow her grandchildren to survive. Just that.

Our off-the-field job is to explain exactly how this is so. Regenerative farming, of any crop, means building healthy soil. For my latest book, I researched metrics on carbon sequestration. A growing body of research suggests that each cubic inch of topsoil we restore of the world’s farmland sequesters up to three billion tons of carbon annually. And hemp’s substantial taproots are absolutely stunning at creating the conditions that allow for the building of topsoil. As Nutiva and RE Botanicals founder John Roulac reminded me, industrial agricultural runoff is the number one polluter of oceans, while regenerative agriculture has the potential to be the leading mode of sequestering atmospheric carbon.

We’re all wise to root for an industry that helps with climate stabilization. If the regenerative farming mode catches on, farmers might even buy us humans a crucial century to get our underlying infrastructural cards in order — the goal being to thrive, rather than panic, as we glide into the post-petroleum future.

It’s hard to beat “saving our grandchildren” as a marketing tool. The real win-win, as we’ve discussed here in an earlier Fine In the Field column, is that regenerative farming wins on performance, the way the peas you pull off your own vines taste sweeter than anything in a market bin. No mass marketed hemp, no matter how pastoral its label, will be able to claim “farmer-owned.” So fear not McCBD in chain drug stores: if the small batch independent regenerative hemp farmer/entrepreneur doesn’t win ‘em on righteousness, she still wins ‘em with a superior product.

Just as they want the finest coffee, craft beer and local bread, millions of folks want the best hemp. Once they understand the value of concepts like bioavailability and organic principles, they won’t want anonymous hemp from flower isolate or fungible grain markets any more than they’d buy their meat at Burger King.

I can attest that regenerative farming is fun, but is it easy, especially for a new farmer? Well, it’s no harder than any farming. Farming, like any job done well, is hard. A lot has to go right over the course of eight months, not least mother nature smiling in a time of climate chaos.The good news is, the sun’s free, and we’ve been given the soil as a bonus gift.

All native soil, I’ve learned care of the wisdom of many colleagues and mentors over the past decade, is composed of an immensely complex microbial neighborhood; one distinct to every ecosystem on the planet – your beneficial microbes, like mycelium, are unique to your farm’s microclimate. That’s a good thing for a lot of reasons – biodiversity and native inputs – these are what our plants want most. Happy plants mean the best hemp products – and unique hemp products are the value-added edge in our top-shelf independent craft hemp marketplace. Think terroir: no hemp will taste or perform exactly like yours just as no two wine vintages are identical. Plus, nurturing native soil microbes is the step that sequesters carbon and saves humanity. In other words, it’s good to have friends in low places.

I, the farmer, get to reap the benefits of robust hemp that’s good friends with the microbes in it soil — already this year’s crop has shrugged off an unseasonable hail barrage here in the Land of Enchantment. This was about a week ago, and when I dashed out at sunrise to the field like a goat kid to stretch, give thanks, and examine the field, everything was predictably irie.

This is why step one for any farmer and farm enterprise is learning how to build their own farm’s soil. Since I’m far from an expert at this, I’m lucky that my goats give tons of manure mixed with organic alfalfa. That’s a breakfast of champions for beneficial microbes. But the first course of action for anyone ready to join the hemp renaissance is to get in the soil: test it, love it, read about it, build it. I suggest keeping good ol’ N, P and K in mind, but also look into the overall organic matter in your soil, with an eye to building the entire beneficial microbial community, especially your mycelium, or fungal community.

In conclusion, you might think you’re a hemp farmer, marketer, or customer. In truth, if survival for the grandkids is the goal, we’re all soil farmers now. And shoppers? Please look at more than price and milligrams of CBD on the label: seek out your region’s farmer-owned products. Make sure your food co-op or grocery store manager knows you’re dedicated to having regional options for regenerative hemp, for vegetables, for toothpaste, for everything. I don’t think you’ll be sorry.

For the regenerative farmer/entrepreneur, hemp is not a get-rich-quick scheme. And yet I’m optimistic for us primates’ making the right decisions at this critical time. Yes, we all recognize that it’s the bottom of the ninth for humanity. But I like to recall that when Edgar and I cooled off by sitting in that blessedly damp hemp field during the 2018 wildfires, that was 500,000 permitted U.S. hemp acres ago. We’ll catch corn, soy, cotton and wheat’s 234 million combined annual acres soon enough – the same way the craft beer is slaying mass market beer, gaining a percentage point per year.

Are you in? Every regeneratively grown acre of hemp counts. We’ve got allies from all kinds of species assisting us. For one thing, all mammals have endo-cannabinoid systems. But I have a feeling it goes beyond that – birds famously love hemp seed, of course. This morning the ravens and hawks were circling even closer than usual while I checked the drip line in the field, and we caught a glimpse of the fox family with whom we’re sharing the Funky Butte Ranch bounty this year.

The soundtrack at this time a year in the high desert is native bees, hummingbirds and woodpeckers, punctuated by a cactus wren trill about every seven seconds. It seems like everybody knows hemp is a superfood and the launchpad for humanity’s recovery and revival. I’m hoping that even rabbits who have built their front door right in our hemp field remember to make our hemp a sometimes food, so there’s plenty for everybody.

Indeed the hemp continues to grow, despite the smoky air. Each morning, I sigh the same sigh of relief that every human has for the 10,000 years of farming before supermarkets: we will survive another year. The joy of seeing the first hemp sprouts emerge and bifurcate is the joy of parenthood. As I mentioned in this passage in the book American Hemp Farmer, “Oxytocin is exchanged, as in any parent-child relationship…We are hemp midwives.” Ask any midwife: it’s a pretty joyous profession to be bringing life into the world. This is no less true when your job is nurturing plants and microbes. Life is life and it is good.

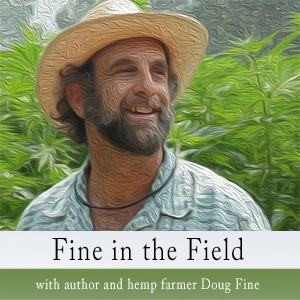

About Doug Fine

Doug Fine is a comedic investigative journalist, bestselling author, and a solar-powered goat herder. His latest book is American Hemp Farmer: Adventures and Misadventures in the Cannabis Trade (Chelsea Green Publishing, April 2020). He has cultivated hemp for food, farm-to-table products and seed-building in four U.S. states, and later this year will be offering an online regenerative hemp course with Acres USA. Willie Nelson calls Doug’s work “a blueprint for the America of the future.” The Washington Post says, “Fine is a storyteller in the mold of Douglas Adams.” A website of Doug’s print, radio and television work, United Nations testimony, and TED Talk is at dougfine.com and his social media handle is @organiccowboy.

The first sprouts — keikis, as folks call babies of all species in Hawaii — have joined the multi-species clan here the Funky Butte Ranch. Accordingly, I have heaved that sigh that all farmers have when they’ve taken the second key step toward superfood security for their families (the first is soil building, which by the way also is the best way to mitigate climate change). Before supermarkets, this was a common sigh. People held festivals and burst forth with prayers of gratitude.

The first sprouts — keikis, as folks call babies of all species in Hawaii — have joined the multi-species clan here the Funky Butte Ranch. Accordingly, I have heaved that sigh that all farmers have when they’ve taken the second key step toward superfood security for their families (the first is soil building, which by the way also is the best way to mitigate climate change). Before supermarkets, this was a common sigh. People held festivals and burst forth with prayers of gratitude.

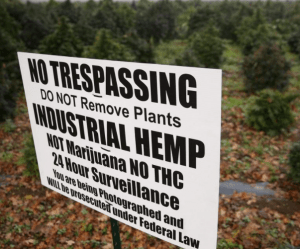

High prices, enthusiastic support from local government and business groups, and looser regulations in the wake of the 2018 Farm Bill passage led to the planting of tens of thousands of new acres of hemp over the last few years.

High prices, enthusiastic support from local government and business groups, and looser regulations in the wake of the 2018 Farm Bill passage led to the planting of tens of thousands of new acres of hemp over the last few years. On April 6, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam signed a bill that defines “industrial hemp extract” as a food. Senate Bill 918, which was introduced by David W. Marsden (D-Fairfax), establishes (i) requirements for the production of an industrial hemp extract or a food containing an extract and (ii) conditions under which a manufacturer of such extract or food shall be considered an approved source. According to the bill, “food” means any article that is intended for human consumption and introduced into commerce. “Industrial hemp extract” is defined as an extract (i) of a Cannabis sativa plant that has a concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) that is no greater than that allowed for hemp by federal law (i.e., <0.3% THC) and (ii) that is intended for human consumption.

On April 6, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam signed a bill that defines “industrial hemp extract” as a food. Senate Bill 918, which was introduced by David W. Marsden (D-Fairfax), establishes (i) requirements for the production of an industrial hemp extract or a food containing an extract and (ii) conditions under which a manufacturer of such extract or food shall be considered an approved source. According to the bill, “food” means any article that is intended for human consumption and introduced into commerce. “Industrial hemp extract” is defined as an extract (i) of a Cannabis sativa plant that has a concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) that is no greater than that allowed for hemp by federal law (i.e., <0.3% THC) and (ii) that is intended for human consumption. PITTSBURG, Kan. — Industrial hemp has seen rapid growth in Kansas since becoming legal in recent years, but could soon be given an even greater boost in the southeast corner of the state.

PITTSBURG, Kan. — Industrial hemp has seen rapid growth in Kansas since becoming legal in recent years, but could soon be given an even greater boost in the southeast corner of the state.