While admittedly still in its infancy, Ben Hartman sees Indiana as well positioned to become a national leader in the burgeoning hemp production industry.

Owner of Clay Bottom Farm, an urban micro-farm located on the city’s north side, Hartman counts himself among the first Hoosier farmers to jump on the hemp bandwagon following passage of the 2018 Farm Bill. That bill legalized industrial hemp production in the U.S.

“We first got our hemp license in 2019, and we grew hemp here at the farm in 2019. This would be what’s considered high-CBD hemp. So, it’s not fiber hemp. It’s the hemp that’s grown for CBD extraction,” Hartman said. “And to make a long story short, it was a huge learning curve, a lot of fun, and overall a success in that we produced several quarts of CBD crude oil out of which we’ve been able to make, and brand, and market CBD tinctures. And we sell those CBD tinctures under the Clay Bottom Farm name through the Maple City Market in Goshen. We’re actually the only local source of that product.”

And according to Bruce Kettler, director of the Indiana State Department of Agriculture, Hartman was by no means alone in entering the hemp market. The latest available data indicates that more than 8,700 acres of hemp were grown outdoors in Indiana in 2019, while another 1.74 million square feet were grown indoors that same year. He noted that 2020’s numbers will not be released until this spring.

Not Marijuana

Hemp, marijuana’s non-psychedelic cousin, includes numerous crop varieties that in turn can be used for the production of multiple products, including CBD oil, food grade oil, grain and hemp fiber. Under current legislation, hemp cannot contain more than 0.3% of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the plant compound most commonly associated with getting a person high.

According to The Brookings Institution, federal law for decades did not differentiate hemp from other cannabis plants, all of which were effectively made illegal in 1937 under the Marijuana Tax Act and formally made illegal in 1970 under the Controlled Substances Act.

That began to change with passage of the 2014 Farm Bill, which reintroduced hemp production to the U.S. farming industry, though that legislation limited the distribution of hemp licenses to a small number of farmers, and growth was restricted to small-scale pilot programs aimed at studying market interest in hemp-derived products.

With passage of the more expansive 2018 Farm Bill four years later, the Office of the Indiana State Chemist, the regulatory body that oversees the state’s hemp program, was cleared to began large-scale distribution of licenses to Hoosier farmers, though they still needed a research proposal and to be associated with a university researcher in order to apply for a license.

“We had quite a bit of growth the last two years, so 2019 and 2020, when we were still in the research phase,” said Don Robison, feed administrator and hemp regulator with the OISC. “What we showed both of those years, though, was a lot of interest, a lot of licensing, a lot of registered acres, but a whole lot less actually planted than what was registered, and I attribute that to a lack of great (seed) sources.

“There are some good sources for plant material and seed, but — and I hate to say it this way — it’s still a little bit of the wild, wild west out there right now,” Robison added. “It’s a new industry, and even good folks that are trying to do the right thing, if they accept too many orders, or they can’t get their plant material to the quality it needs to get to, stuff like that can come back to bite them.”

Speaking to challenges within the industry, Marguerite Bolt, hemp extension specialist with the Purdue University Department of Agronomy, noted that one of the biggest challenges currently facing Indiana’s hemp industry is simply the fact that it is so young.

“This industry in particular just seems to be somewhat volatile, you know, because it’s developing. That’s probably one of the biggest factors, is it’s just very new, and we’re trying to understand where the market is going to go, what consumer demand is, etc. It just gets pretty complicated,” Bolt said. “And then, of course, regulatory changes make it an even more challenging plant to work with, because it seems like things are constantly changing when we look at rules and regulations.

“And for these growers, they have a lot on their plates already, and they’re trying to navigate this industry, and figure out who is buying, who is selling, what the potential looks like for them, etc.,” she added of the issue. “With these constant changes, I think, if I were a grower, it’s a huge deterrent.”

Overproduction

Robison pointed to oversupply and profitability — particularly in the area of CBD production — as another major challenge facing the state’s hemp industry.

“As far as acres of hemp production, CBD is by far the majority, accounting for probably about 85% of the total number of acres being planted,” Robison said. “That’s going to eventually have to change for profitability to really come into the market, because that’s where all of the oversupply is.

“The first people into the industry were making obscene amounts of money, and so that’s what got everybody involved in it, what got everybody interested,” Robison added. “That in turn resulted in a lot of non-farmers getting involved, people who didn’t have any farming experience, and now they’re having their own issues kind of learning how plants work with soil and fertilizer, that type of thing.”

Kettler agreed.

“I think we saw a lot of people who jumped into this really big, and the seed is expensive. It’s a new crop. So, we’ve got to learn how to grow it, we’ve got to understand the pests that can affect it, etc. So, it’s one of those things that I would encourage people not to jump into too hard, just because of the fact that they could lose a lot of money,” Kettler said. “All that is to say, what we are encouraging people to do is, make sure you have a contract for the outlet of your production before you plant. If you’re producing for CBD, for example, get a contract with somebody that’s going to process it for CBD. And the same is true if it’s being grown for fiber, etc. Make sure you have a contract in place that allows you to know you’ve got a way to take that production and do something with it, and market it, so that you’re protected a little bit.”

Still growing

Looking forward to the 2021 growing season and beyond, Robison is predicting continued growth within the state’s hemp industry, though likely at a less fervent and ultimately more manageable pace than had been seen in the crop’s 2019 and 2020 seasons.

A big reason for that prediction, he said, is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s recent decision to approve the Indiana State Hemp Plan for commercially growing and processing hemp.

According to Robison, the new plan, approved by the USDA in October 2020, takes OISC’s pilot hemp program and transitions it to a commercial hemp production program, granting the OISC greater regulatory authority and the ability to clearly define the rules and regulations around hemp production and processing in Indiana.

Under the plan, Indiana farmers are no longer required to have a research component to be licensed. In addition, farmers are now eligible to include hemp in crop insurance, which gives them a bit more stability when it comes to the potential risks of growing the new crop.

However, in a change from free licenses in past years, those seeking licenses for the 2021 growing season will be charged a $750 application fee for either handlers or growers, or $1,500 for both.

While the primary goal of the new fee is to help the OISC cover its expenses connected to administering the state’s hemp program, which it is required to do under state statute, Robison said he also anticipates the fee could help curb some of the oversupply issues the state saw during the 2019 and 2020 growing seasons.

“And it looks like those that are licensing for 2021, so far those acres of production are way down for 2021. So, what that tells me is, the growers are realizing that there’s oversupply. They’re trying to grow one acre instead of five, or, if they’re growing fiber or for seed oil or for grain, they’re growing 10 acres instead of 20 or 30,” he added. “So, we’re seeing those kinds of positive growth signs amidst the negative of low prices, oversupply and some questionable suppliers. We’re starting to see the market shake out a little bit, which is a really good sign.”

The future

As for what Indiana’s hemp industry might look like in another five to 10 years, Robison said he anticipates what will likely be a gradual shift away from the current dominance of CBD production to an industry more focused on hemp grain and fiber production.

“I anticipate, and I hope, that Indiana’s market moves away from so many acres of CBD, just because of the oversupply problem, and moves instead toward grain and fiber,” Robison said. “Indiana’s growers already have the necessary equipment, and they’ve already got ways to process fiber and grain. So, I think that’s the place we’re going to settle in. There will still be CBD suppliers, but I think there will be many less CBD suppliers in five to 10 years than there are now.”

Bolt also noted that she anticipates hemp will always remain a niche crop in Indiana, rather than completely replacing the more traditional crops, such as corn and soybeans.

“At the university, and I think in the industry as a whole, a lot of us are trying to promote hemp as a diversification tool. So, not looking at it as, ‘I’m going to switch my farm to a hemp-only farm.’ We’d rather see, ‘how can I fit hemp into my current operation so I have more diversification,’ which economically is a good thing,” Bolt said. “It also provides some security, where if you have a crop failure one year, you’re not only relying on that specific crop. You have multiple rotations, fields planted in other crops, etc. So, that has kind of been my perspective as well. Basically, figure out how it fits into your system, and don’t do a complete overhaul just to grow hemp. Make it work for you.”

While only time will tell what the state’s dominant hemp crop will eventually end up looking like, Hartman said he’s confident that hemp production will continue in Indiana.

“It will definitely always be a niche crop, but it’s definitely here to stay, too. I don’t see the laws becoming more regressive. I see them opening up, especially as people become more familiar with the plant, and learn new ways to grow it that are safe and legal,” Hartman said, noting that while Clay Bottom Farm’s existing CBD oil supply should last him through the remainder of this year, he does plan on planting another hemp crop in 2022. “Indiana is actually ideally situated in terms of climate. Our climate is just ideal, and our soils are ideal for hemp production, too. So, I can see Indiana as being a real leader in hemp production.”

Aaron Rink, a fellow Goshen farmer and former partner with a large hemp farm operation in the Millersburg/New Paris area, is also optimistic about the future of hemp.

“I would say Indiana definitely has a future with hemp,” said Rink, who, while having exited the hemp production industry back in early 2020 due to personal reasons, is still a big supporter of the crop. “I know that the CBD oil market has peaked … but I still think there is a future and a market for hemp, particularly on the fiber side. What all can be raised fiber-wise, and what can be done with it, I still think there are things that haven’t even been invented yet that are going to require hemp. So, I think that’s pretty cool.”

On Monday October 4th, Governor Gavin Newsom signed SB 292 (Wilk), the CHC sponsored measure that will conform California statutes regulating the reporting and testing of industrial hemp to the new requirements established under the United States Department of Agriculture interim and final rule, including provisions to align the California Food and Agricultural Code, California Department of Food and Agriculture regulations and the State Plan with the federal requirements.

On Monday October 4th, Governor Gavin Newsom signed SB 292 (Wilk), the CHC sponsored measure that will conform California statutes regulating the reporting and testing of industrial hemp to the new requirements established under the United States Department of Agriculture interim and final rule, including provisions to align the California Food and Agricultural Code, California Department of Food and Agriculture regulations and the State Plan with the federal requirements. Our multiyear effort to address the issuance of a California Department of Public Health (CDPH)

Our multiyear effort to address the issuance of a California Department of Public Health (CDPH) ![items.[0].image.alt](https://www.votehemp.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Blank.gif)

![items.[0].image.alt](https://ewscripps.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/8fea658/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1280x720+0+0/resize/1280x720!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fewscripps-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F61%2F4b%2Fb9f6a09247799060bea78cd8e5c5%2Fdownload-1.jpeg)

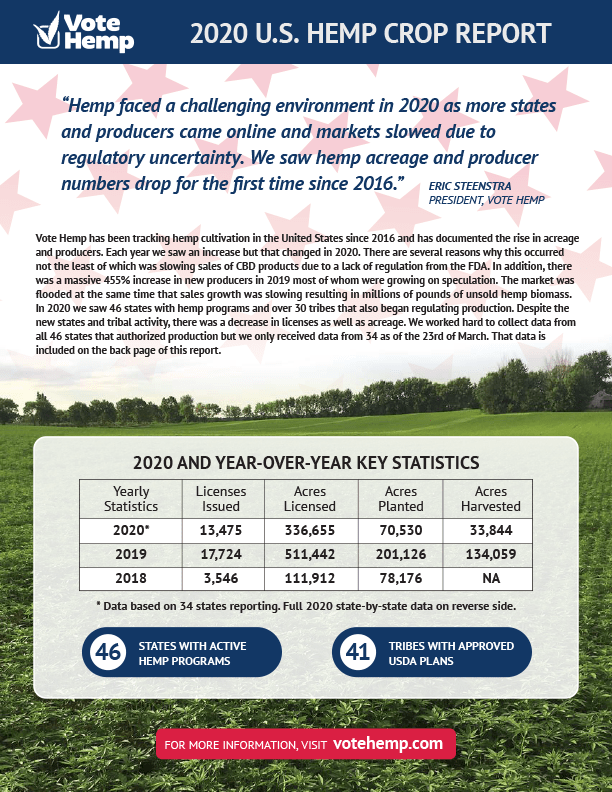

Washington, DC – Vote Hemp has released its 2020 Hemp Crop Report documenting the state regulated cultivation of hemp in the United States. Vote Hemp has been producing the Hemp Crop Report since 2016 and the 2020 growing season marks the first time that there has been a decrease in licenses and acreage. Going into the 2020 season, there were 49 states that had passed laws authorizing hemp farming and 46 of those have regulatory policies or plans to allow hemp to be grown.

Washington, DC – Vote Hemp has released its 2020 Hemp Crop Report documenting the state regulated cultivation of hemp in the United States. Vote Hemp has been producing the Hemp Crop Report since 2016 and the 2020 growing season marks the first time that there has been a decrease in licenses and acreage. Going into the 2020 season, there were 49 states that had passed laws authorizing hemp farming and 46 of those have regulatory policies or plans to allow hemp to be grown.